Dolls are more than childrens’ toys. They are small embodiments of our cultural values, fundamental tools for early childhood development, and can even champion women’s empowerment.

In the small village of Andahuaylillas, located in the rural highlands of the Peruvian Andes Mountains, the Q’ewar Project is creating sustainable employment for women through the art of handmade doll-making.

In Andean villages like Andahuaylillas, where the local economy is largely based on agriculture, it can be difficult for women to secure a source of income that doesn’t require them to do back-breaking work out in the fields, under the sun, with a shovel in hand. Meanwhile, the Project has allowed women in the village, many of whom never had a doll growing up, to earn a decent salary making dolls, sewing clothes, dressing the dolls and braiding their hair.

Some of the dolls are blond-haired and blue-eyed, and are dressed in a more Anglo-European attire, as these dolls sell best abroad, but others look like the Project’s women, dressed in the traditional Ñusta worn for special celebrations in the Peruvian highlands or with a manta Andina on their back to carry their baby.

Launched in 2002, the Q’ewar Proyect’s mission is to create “an atmosphere which fosters self-esteem, personal growth, and a way to gain economic independence by learning life skills in a community setting.” Little-by-little it is achieving its mission.

In addition to a comfortable work environment, the Project offers a competitive salary. Q’ewar has consistently paid wages that are above average. In its early days, the Project paid the women six soles a day, while in the fields they were only paid five soles. Today, the women earn 41 soles per day, compared to the average local salary of 39 soles.

In this way, the Project has fostered financial independence among many of the village’s women. Several of the women that have passed through the Project over the past 22 years have managed to buy or build their own homes, while others have installed bathrooms. Other women have taken the experience and have ventured off to start their own businesses, such as tamales sales. This financial independence has also allowed several of the Project’s women to leave abusive relationships, as they no longer depend on their partners to provide for their children.

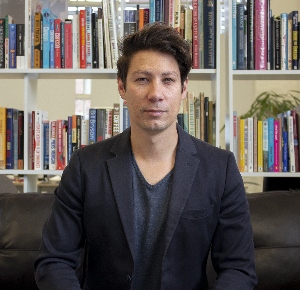

Q’ewar Project Director Julio Herrera estimates that 40 families have benefited directly from the Project, while another 120 families in the village have benefitted indirectly over the years.

There are currently 26 women working at the Q’ewar Project full time in the doll-making and felting workshops. Five of these women have been with the Project since its inception.

The Project also employs two kindergarten teachers to work at the Wawa Munakuy Waldorf school, the name means “for the love of the children” in Quechua, the language of the Incas, which is spoken throughout the Sacred Valley. The young children of the Project’s women are invited to study at the school, as are the children of the village’s most underprivileged families. The school´s activities include bread making, music, art and nature activities.

At least 210 children have passed through Wawa Munakuy over the years, some of them are now grown professionals.

In addition to its doll-making and educational activities, the Project also employs three men to help with construction and organic self-sustainable farming activities. The Project cultivates small plots of corn, quinoa, wheat, beans, rye, peach trees, as well as some vegetables for domestic consumption.

But no vision as great as that of the Q’ewar Project comes without its fair share of challenges. Inflation has driven up costs, however, the Project has made a concerted effort to maintain the original price of its dolls. And, as mentioned, the Project has continuously offered salaries above the local average. Salaries are almost seven times higher than they were when the Project began. As a result, the Project is currently navigating some economic difficulties.

Herrera says his long-term vision for the Q’ewar Project is for it to continue empowering the local women and, when it comes time for him and his wife Lucy to retire, to pass the administrative keys on to the Project’s women.